Library dedicated to Claude Lévi-Strauss

This installation is the intersection between a conversation I had with David of the Waunana tribe in the Choko rainforest in Columbia, South America in 1986, and the critique that Lévi-Strauss expressed about writing’s civilizational importance in his seminal book ‘Tristes Tropiques’.

The time I spent with the Waunana on the banks of the San Juan river and my attempts to comprehend and understand their culture and the role of the shaman, brought me to the realisation that my questions appeared to determine the answers.

I realized how much the language I was communicating in was determining what I was perceiving, the extent to which what I saw, thought and understood was more a projection of my culture and ‘civilisation’ than what I was actually observing. The tools of investigation and enquiry determined the outcome.

Even more destabilising was the realisation that contrary to what I would have expected, David did not appear to feel threatened by the explanations I gave him when he asked me about the sun, the wind, and other natural phenomena. From his reactions I could tell he was quite amused by my scientific explanations, authoritative to me, yet somehow only a further elaboration to his cosmologie and not to the exclusion of his own belief system. As Levi Strauss stated ’instead of treating the whites as a foreign body, the Indians integrated them into their system of thought’ (1). As I explained the earth’s movement around the sun, the heating and cooling of the earth and the effect on the movement of air and the resulting wind, the sun began to set, David turned his head to observe this every day dramatic event and commented with a smile “it’s a funny thing science”.

In his famous book about his travels into the Brazilian interior during the thirties, Levi Strauss describes his skepticism about the importance we ascribe to writing as a civilisational instrument.

During his stay with the Nambikwara he observes the mimicking of his, Levis Strauss’, writing and noting by their chief who appears to want to heighten his authority in the eyes of his tribe through this appropriation.

Levi Strauss concludes: ’By accessing knowledge crammed into libraries, these people make themselves vulnerable to the lies that printed materials propagate in even greater proportion. The die is probably cast. But in my Nambikwara village, the strong heads were even the wisest. Those who disassociated themselves from their chief after he tried to play the civilisation card (after my visit he was abandoned by most of his people) were confusedly aware that writing and perfidy were entering their homes together’. (2)

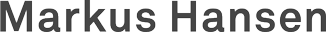

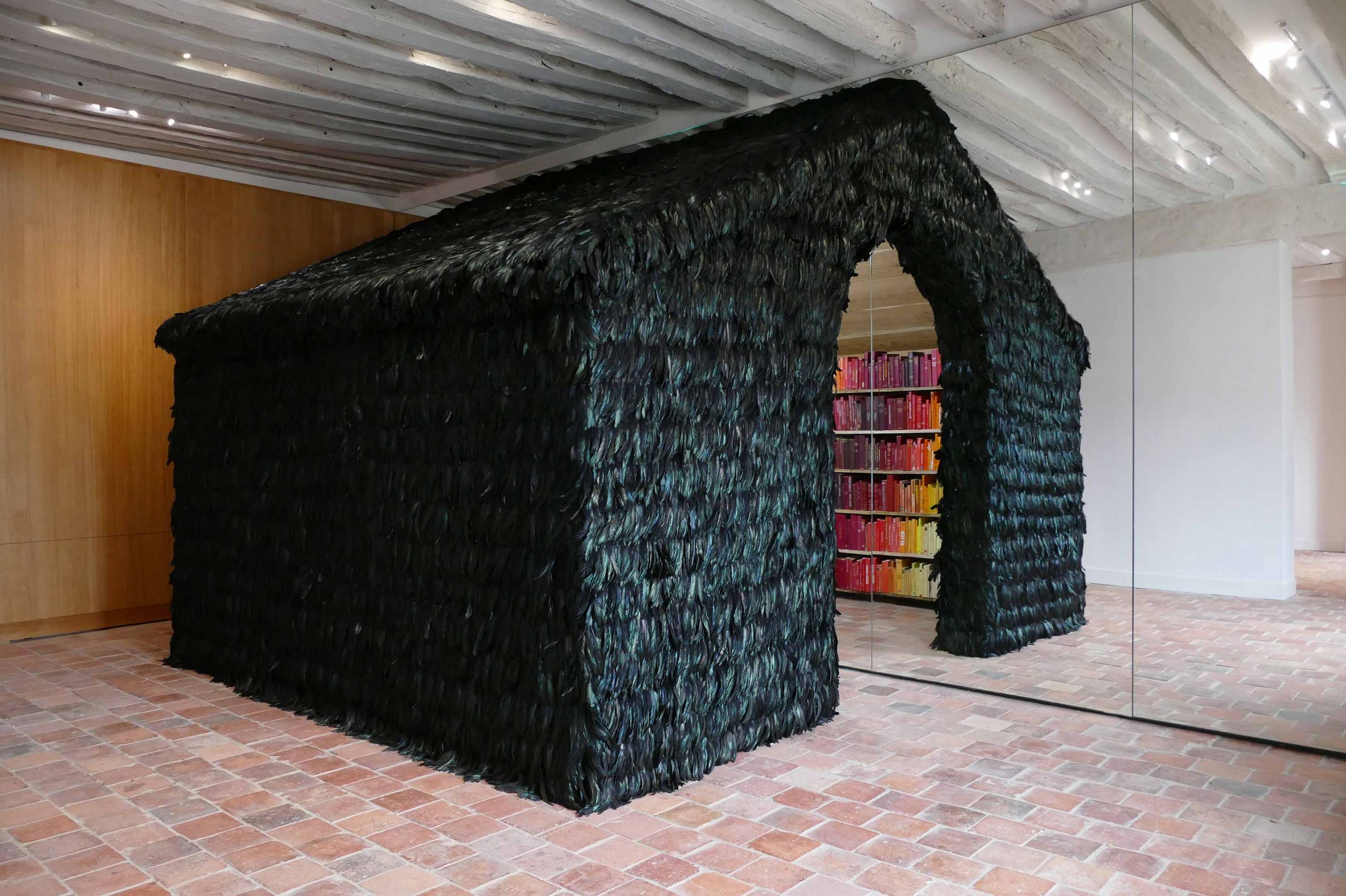

The Bibliothèque for Claude Levi Strauss could be equally dedicated to the Nambikwara and to David of the Waunana. It consists of a fully mirrored wall reflecting half a feathered cabin to create the illusion of a whole cabin. The exterior is covered with black, lightly iridescent and yet light absorbing feathers. The incongruity of this natural material as an exterior architectural skin, both attractive and repulsive, houses and echoes the inversion of hierarchies on the inside of the cabin, playing with our habitual formula of nature versus culture.

The interior is panelled in American oak, with shelves of books that are ordered chromatically, each row of books slightly shifting to create colour gradations from green to yellow to orange to red to blue. The colour of the book’s spines takes complete precedence over title, subject and author to determine the order. Colour as a value, an order, though scientifically objective, can not be fixed or located ideologically or intellectually, yet stimulates us emotionally and triggers our deepest subjectivity. Furthermore this new order juxtaposes the titles in a seemingly random manner, subverting any notion of literary categorisation and thereby generating a new cultural reading. This library deconstructs or rather reconstructs our usual and binary representations of nature versus culture.

The mirror doubles the space, dramatises the chromatic effect and simultaneously limits it as an illusion, hinting at the vain authority we accord the verb and our subjective interpretation of our cosmologie, that of the so-called civilised world.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Foreword Chroniques d’une conquête dans Ethnies numero 14, 1993

Claude Lévis-Strauss, Les Nambikwara, Tristes Tropiques 1955, Plon

Une bibliothèque pour Claude Lévi-Strauss

Cette installation est le croisement d’une conversation que j’ai eue avec un nommé David de la tribu des Waunana dans la forêt tropicale du Choko en Colombie en 1986 avec une lecture plus récente, celle de la critique que Lévi-Strauss émet au sujet de l’écriture dans « Tristes Tropiques ».

Les deux mois que j’ai passés avec les Waunana sur les rives du fleuve San Juan et mes tentatives pour approcher leur culture m’ont fait prendre conscience que mes questions déterminaient les réponses. La langue dans laquelle je m’exprimais déterminait ce que je percevais, j’ai alors commencé à mesurer à quel point ce que je voyais, pensais et croyais comprendre était davantage une projection de ma culture que de ce que j’observais. Mes outils d’investigation orientaient les résultats de mon enquête.

Mais ce qui m’a vraiment surpris c’est que, contrairement à ce que je craignais, David ne semblait pas troublé par les explications que je lui donnais quand il m’interrogeait sur le soleil, le vent ou d’autres phénomènes naturels. Il paraissait plutôt amusé par ces raisonnements scientifiques qui pour moi faisaient autorité. Comme l’a écrit Lévi-Strauss : « Au lieu de traiter les Blancs comme un corps étranger, les Indiens les ont intégrés dans leur système de pensée” (1). Alors que j’expliquais le mouvement de notre planète autour du soleil, le réchauffement et le refroidissement de la terre, l’effet sur les marées et l’effet sur les vents et les marées, le soleil a commencé à descendre dans les arbres. David a tourné la tête pour observer cet événement à la fois spectaculaire et quotidien et, en continuant de sourire, a murmuré : « Drôle de chose, la science…”

Dans son livre qui relate ses voyages à l’intérieur du Brésil dans les années Trente, Lévi-Strauss exprime son scepticisme quant à l’importance que nous accordons à l’écriture en tant qu’instrument de civilisation. Pendant son séjour chez les Nambikwara, il remarque que le chef de la tribu l’imite copie ses geste quand il prend ses notes mais le chef de la tribu ne sait pas écrire et Levi-Strauss le soupçonne de vouloir ainsi assoir un peu plus son autorité aux yeux de sa tribu. Et Lévi-Strauss de conclure : « En accédant au savoir entassé dans les bibliothèques, ces personnes se rendent vulnérables aux mensonges que les imprimés propagent dans une proportion encore plus grande. Les dés sont probablement jetés. Mais dans mon village de Nambikwara, les fortes têtes étaient même les plus sages. Ceux qui se sont désolidarisés de leur chef après qu’il ait essayé de jouer la carte de la civilisation ( après ma visite, il a été abandonné par la plupart des siens) étaient confusément conscients que l’écriture et la perfidie entraient ensemble dans leurs maisons. » (2)

C’est pourquoi, la Bibliothèque de Lévi-Strauss pourrait être dédiée aux Nambikwara au milieu desquels il a vécu ainsi qu’à mon ami David des Waunana.

Elle se compose d’un mur tout en miroir reflétant une cabane en plumes, on a l’illusion d’une cabane entière mais il n’y en a qu’une moitié qui n’est complète que grâce à son reflet… Les faces externes sont tapissées de plumes noires ( plumes de coq), légèrement irisées et absorbant la lumière, ça attire, on aurait envie de toucher, caresser mais en même temps, ça repousse, ça dégouterait presque comme un matériau inconnu, mystérieux. L’incongruité de ce matériau « naturel » comme peau architecturale abrite et fait écho à l’inversion des hiérarchies à l’intérieur. On entre et on est cerné d’étagères construites en planches de chêne américain peu dégrossies remplies de livres qui sont rangés en fonction de la couleur de leur couverture. L’oeil glisse sur ces variations chromatiques, des couleurs chaudes aux couleurs froides et puis l’inverse, le miroir produit aussi son effet à l’intérieur, démultipliant ces déclinaisons et produisant un effet de kaléidoscope. C’est la couleur du dos qui importe et non le titre, le sujet ou l’auteur, ce sont les couleurs qui ordonnent la composition générale. La couleur en tant que valeur, même si elle est scientifiquement définissable, est moins « épinglable » idéologiquement ou intellectuellement que les mots, les titres ou les noms mais elle nous touche émotionnellement et atteint notre sensibilité d’une autre manière. Ce nouvel ordre subvertit ainsi toute notion de catégorisation littéraire et invite à un autre regard. Cette bibliothèque déconstruit ou plutôt reconstruit nos représentations habituelles et binaires de la nature versus la culture. Le miroir dramatise l’effet chromatique et le limite en même temps puisqu’il s’agit seulement d’une illusion. La bibliothèque-cabane de Lévi-Strauss interroge l’autorité que nous accordons au verbe et relativise notre cosmologie, celle du monde dit civilisé.

1 – Claude Lévi-Strauss, Avant-propos Chroniques d’une conquête dans Ethnies numero 14, 1993

2 – Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes Tropiques, Les Nambikwara, Plon, 1955